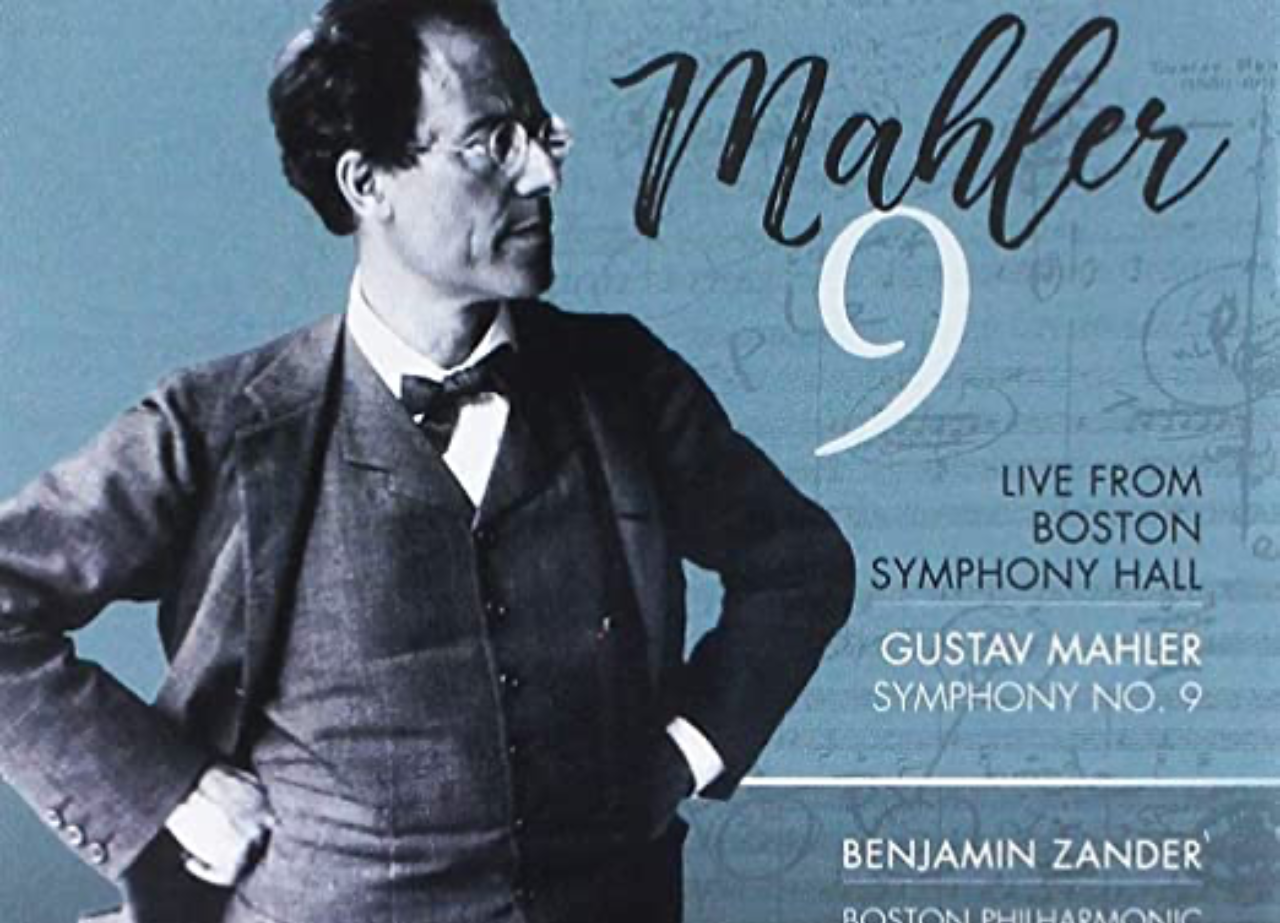

Benjamin Zander’s New Mahler Ninth

Scheduled for release on February 22, this is a follow-up to Zander’s 2017 recording of the Mahler Sixth with the same orchestra, which received good reviews. Like most Mahler Ninths issued outside of a complete cycle, it is spread over two discs because it just barely makes it over the time limit to fit on one (86:11), and contains no filler material.

Zander has an awfully good publicity machine that praises him as one of the greatest conductors of his time, but my own personal experience with several of his previous releases (other Mahler symphonies) tell me otherwise. His first recording of Mahler’s Sixth with the Philharmonia Orchestra was full of errors, and his 2013 recording of the Mahler Second I found to be lacking in inner fire and drive, though it was well played. His first recording of the Ninth, also with the Philharmonia (Telarc CD-80527) was nominated for a Grammy Award, but as I pointed out in my article on such matters (No Phony Awards Here), the Grammys are full of corruption, graft and favoritism, thus I take any of their nominees and winners with a huge grain of salt—sometimes, a whole barrelful. (Other reviewers may try to snow you, but after a half-century of reviewing, unfortunately I know the truth.) On the other hand, his later recording of the Sixth with this same orchestra a few years ago received excellent reviews, thus I decided to give this recording of the Ninth a try.

The Ninth Symphony, like the Third and the Seventh, is actually quite difficult to pull off well. It requires not just a long view of the entire score as musical architecture but also a moment-by-moment emotional involvement that goes beyond the notes. On the other hand, a too-hysterical reading with overdone italicizing of phrases à la Leonard Bernstein takes it too far, thus a certain balance is required. The very opening of this performance, though quietly played as per the score, seemed to me to lack a certain amount of feeling that I hear in two of my favorite recordings of this work, John Barbirolli’s reading with the Berlin Philharmonic and one that may surprise some people, Georg Solti’s recording with the Chicago Symphony. The latter is still my all-time favorite performance. The other recordings I like very much are Bernard Haitink’s later recording with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra on BR Klassik and Michael Gielen’s performance with the SWR Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden und Freiburg, recently reissued in a complete Mahler set.

But this one really grows on you as you listen to it—at least, it did for me. The musicians of the Boston Philharmonic Youth Orchestra have both the positive and negative qualities that so many young players exhibit. Among the positives are exceptional technique, a full grasp of the score from start to finish and an enthusiasm in playing music they particularly enjoy. Among the negatives, and they are few in this case, are a tendency to gloss over the more tragic moments in the score, in part (I am sure) because they’ve never experienced any tragedy in their lives except, perhaps, an inability to pay off their student college loans. Deeper, more personal tragedies elude them whereas they did not elude Mahler.

That being said, Zander seems to have been able to infuse some feeling into this orchestra although the occasional glib moments come and go without, fortunately, dominating the performance. There are many moments in this performance where they really sink their teeth into the music, get under its skin and make the listener’s skin tingle as when I listen to the Solti, Gielen, Haitink and Barbirolli performances (in that order). More interestingly, the engineering of this recording is absolutely astounding. Even played from downloads through my computer speakers (and I have what is generally considered the best brand of computer speakers, the Klipsch IHX, but still, they don’t have the middle or low-range richness of my big ole Panasonic floor speaks for my main stereo system), there is incredible depth to the sound, almost as if one were actually sitting in row 4 or 5 in a concert hall and taking it all in. I should point out that not all conductors achieve this kind of balance. As much as I love the Solti performance, for instance, he created the classical version of Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” with the Chicago Symphony, which gives the listener an entirely different perspective. (Haitink essentially did the same with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra.) Barbirolli achieved some depth with the Berlin forces in 1964 and Gielen did a little better with his SWR orchestra in digital sound, but in this performance by Zander you really hear this symphony as if it were being played in “layers,” yet at the same time the orchestra coalesces when it needs to in order to create powerful climaxes. One might liken this, in a way, to the bellows of an accordion: a solid mass when pushed together but spatial and expansive when opened up all the way. Sorry if this seems a silly metaphor, but except perhaps for the ever-expanding universe I can’t think of a better one at the moment.

Among the outstanding moments in this performance is the French horn-flute duet around the 24-minute mark in the first movement, which will give you a good idea why I like it so. When was the last time you really paid attention to this passage, or that it grabbed you as a significant moment or detail? The soft wind passage at 26:35 is yet another such moment. The Boston Youth players really capture the moment here, and as your ears and mind wander through this symphony you’ll find that they capture many more such moments.

And yes, I will give Zander a great deal of credit for this, which means that either he has himself grown as an artist (always possible) or has, at long last, found exactly the right orchestra to pick up on what is trying to convey in Mahler. I have no idea if these two recordings (the Sixth and the Ninth) are harbingers of a complete Mahler cycle with this orchestra, but provided that they find and use top-tier vocalists in the second, third and fourth symphonies, I hope it is.

In the second movement, Zander and the orchestra don’t quite pull off the somewhat madcap feeling that one heard from Solti and Gielen, but that is artistic choice. In terms of tempo and phrasing, it is very much a “classic” ländler, and in the middle section the orchestra does play with gusto. By the 3:45 mark, they are clearly into the spirit of the piece, and stay there for a while. And listen to the crisp, accurate playing of the French horns in their rapid triplet passages! Wunderbar! Prima ganz! Tip top! [I have just exhausted my knowledge of enthusiastic German terms.] And once again—if one is following along with the score—you will be amazed at how accurately the orchestra plays this music. Now, we all know that Mahler himself “fooled around” with tempo and phrasing when he performed his own symphonies; look at his marked-up scores in the New York Philharmonic archives for proof of this; and I have said on many occasions that Mahler is the only great composer in my experience whose music can withstand a number of varied approaches in tempo and phrasing so long as they are not ridiculous or out of all proportion to the score. Nonetheless, it is absolutely refreshing to hear a performance that sticks pretty much to what the composer wrote and yet can still find the right spirit at almost every moment.

Now, I can imagine that the reactionaries out there will complain that the digital sound of this release is too “clinical” and not “warm enough” for Mahler. I admit that it doesn’t have the warmth of the Barbirolli-Berlin recording or even as much as Solti-Chicago, but in my opinion this is more due to the extremely clean playing of the orchestra per se and not toe engineering. There is, if you listen through headphones, plenty of hall ambience here to allow the instruments proper resonance, but both the 1964 Berlin Philharmonic and the 1978 Chicago Symphony were orchestras built for warmth of sound in addition to their other fine qualities. Like so many modern (and especially young) orchestras nowadays, this Boston Youth Philharmonic seems built for cleanliness of sound, thus although there are moments of rich textures to be heard here and there in the performance, it is clarity and cleanliness that are the overriding qualities of their sound profile. It’s just the way this orchestra plays and, as I say, it intrigues and thrills me. In the last movement, they fully capture the sadness and longing that Mahler put into it.

And the orchestra really does pull all the stops out in the Rondo—Burleske, reveling in the music’s grotesqueries without distorting a single note or phrase. It’s quite amazing, really.

For all of you who thought that the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra, when it was conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, was just the berries as a young musical aggregation, you need to hear this recording. It’s really an impressive achievement.

Click here to listen to Mahler’s Symphony no. 9.